Click here to download the PDF version of the synthesis

Teaching of religion, secularism and interreligious dialogue: crossed views in France and West Africa.

Chat on June 21, 2019 organized by the Africa World Institute

Speakers :

- Dr René NOUAILHAT, Professor of Universities, historian of religions, founder of the Institute for the Study and Teaching of Religions at the Catholic University Centre of Burgundy.

- Father Basil SOYOYE, Nigerian Missionary of the Society of African Missions (SMA) of Lyon, Director of the Crossroads of African Cultures. Missionary formator and seminarian in Egypt, Benin and France.

The talk on the religious fact opens with some remarks by Professor René Nouailhat on the few differences in the teaching of religious facts in West Africa and France. Passionate about the religious phenomenon, Dr. Nouailhat conducted his research as part of his state thesis on the beginnings of Christianity.

He then focused on transmission problems. The first observation he made when he arrived in Kati (Mali) as a teacher was as follows: Practice is different from theory. He therefore understands that we must start from those with whom we are speaking, rather than from scholarly knowledge. In this way, to put oneself within the reach of those to whom one teaches.

When he started teaching in France, he found nothing in the textbooks about the richness of religious education, it was only partially transcribed and simplified. Indeed, Mr. Nouailhat noted that there was no information as to the sources of transmission of religious education. For example: who wrote the Koran? For how long? Questions that remain unanswered, for him, in school textbooks. There are also religions that are not addressed, such as Judaism, which is first mentioned only through the Dreyfus case.

As a former headmaster in Catholic education, his interest lies in the transmission of this knowledge. It is deficient in science, because according to him metaphysics irrigates physics and should be present in a “history of science”. The same negative observation in the Letters: Prayers being part of literature, why this bias to exclude religions in the study of literary genres?

An official mission in Catholic education is entrusted to it by the General Secretariat on the question of the teaching of religion. It has also opened new avenues for the Centre universitaire catholique de Bourgogne and the religious education courses it has created there have been recognized by the Ministry of National Education to deliver a Master’s degree.

“Today, the situation is much worse.”

A total deadlock is made on the teaching of religion in France according to him. Régis Debray’s report on this subject, commissioned by Jacques Lang, is now obsolete and denied by the decisions of the national education ministers. René Nouailhat thus denounces a “secularism lobbying” within the national education system. This criticism is detailed in his book “La Leçon de Malicornay”. He concludes that it is not easy today to talk about religion in education.

“Teaching religion is a challenge.”

The observation made earlier leads to another question: Why is it so complicated to talk about religion in school? Today, the education provided in schools is secular, does that mean that the religious fact should not be addressed?

The genesis of secularism

“It’s a word that’s only spoken of with fury and noise.”

Secularism is ambiguous, we do not know how to situate it. Professor Nouailhat believes that this is a contradictory term, used both repressively and permissively. The example of the case of young girls wearing veils in Epinal illustrates his remarks, in 1989, when they appeared veiled, it was necessary to accept the situation in the name of secularism or to refuse it in the name of secularism. It is therefore a cleavage concept. What about the abolition of nurseries in town halls? The inhabitants of the cities of Provence (with the tradition of the santons) do not share the desire to abolish the latter and are surprised at the latest decisions rendered by the administration on this subject.

There are two ways to write the word “lay”.

- Spelt as follows: “Lay” – reference to the Catholic world, this refers to someone who is not a priest. It is a secular separation (the separation of the spiritual order from the temporal order). In the Republic it is a secularism of separation of Church and State.

- Spelt as follows: Secular – comes from the Greek Laos which refers to the people without distinction, regardless of divisions. This is what gave secularism in the republican sense of the word, but we are in the secularism of integration.

The school is crossed by both secularities. There is a separation of domains but the integration of all people. Secularism in schools will be complicated because the combination of these two aspects of secularism creates a situation that is unmanageable for school heads.

To understand secularism and its relationship to religion, it would be wise to revisit the definition of the term “religion”. It is a heritage of the Latin world where religion was not associated with faith. The word faith comes from the Latin “fides” which means to rely on someone. Religion was a civic affair in Rome. We did not speak of conviction but of faith because religion had a neutral connotation. Later, this term characterized imperial Christianity.

All religions are lived in the plural but are called singular. Religions are scattered and fragmented, but in the way they are talked about, this aspect of religion is not very visible. Nowadays, there are identity reflexes and closures that lead to a hardening.

Once these different terms have been defined, it is appropriate to consider the “religious dimension of the facts”, what is meant by religious fact?

For René Nouailhat, the expression “religious facts”, popularized by Régis Debray’s report, was likely to reassure the laity, but we must not stop there. Religious facts” have a religious dimension that prevents us from confining ourselves only to facts, i. e. to descriptions. The meaning experienced in and by these facts must be taken into account to understand them.

School pedagogy is very complicated, you have to be careful how the facts are told. There is a didactics of the “religious fact” that must be set up according to the disciplines to help develop a critical mind.

The conditions for the appropriation of religious heritage, a heritage that belongs to everyone, are at stake. A question arises from this development: how can we welcome the foreigner if we are foreign to ourselves?

After these remarks by Professor Nouailhat in order to establish a clearer vision of the religious fact and its teaching, it is Father Basil’s turn to share his practical experience with the audience. Father Soye is a member of the Société des Missions Africaines, he is also the director of the Carrefour des Cultures Africaines based in Lyon. The Crossroads of African Cultures was born from the desire to take African values and try to put them in dialogue with other values. He presents the different issues raised by this talk.

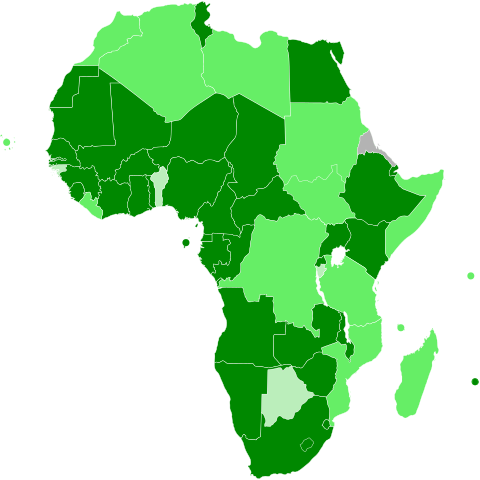

Secularism and interreligious dialogue are not lived in the same way in Africa as in France. There are 14 countries in Africa that include the term secularism in their constitutions (Mali, Senegal, CI…). What does that mean? There are three possible secularities:

- Those of researchers, it is about the separation of the religious, spiritual, political…)

- Those of the rulers, who interpret them according to the circumstances

- That of the mass of the population, this last category does not really know what this term means.

A remark was made by Father Soyoye, “Do they adhere to the principle of secularism in all three cases ? There are circumstances that do not clarify the issue”.

He notes that in the Anglo-Saxon world in Africa, there is no real equivalent to translate the word secular. We speak of “secular” states as is the case in Nigeria. We then try to maintain an equitable proportion between the different religions. That is, the State subsidizes pilgrimages of all religions, so a citizen who wants to go to Mecca is just as likely to have his pilgrimage financed as another who wants to go to Jerusalem, for example. By observing this phenomenon which takes place in these African States, another observation is made during this talk: it is not the secular/laic conception found in France.

The faith taught in private education in general

Continuing with the example of the Anglo-Saxon states in West Africa, Nigeria being the most striking example: From primary school to university, a faith orientation is maintained, the great evangelical churches have great schools. Among Nigerians, faith is taught at the university and all students must attend the teachings given in this regard. Freedom lies in choice: anyone can choose whether or not to go to this school. However, this great freedom of choice has given extremists the opportunity to have their own school and to establish their beliefs in a sustainable way. As a result, interfaith dialogue in Nigeria has become more complex.

The creation of “Boko Haram” stems from this liberal vision of religious education. Its founder Mohamed Youssouf started as a teacher in a Koranic school. A part of the population, aware of the excesses of state education, (according to them, corrupt and unruly statesmen are the very product of this education) has seen an alternative in this new religious approach. Thus, they thought they were securing their children’s future in a dimension of integrity. One of the factors that encouraged adherence to this “school” was the safety and well-being of their descendants. After Youssouf’s death, the group was weakened, which left the door open to other influences and abuses. The founders of Boko Harram are no longer, the principles that led to the foundation of this school have definitely disappeared.

The second challenge for Father Soye, when we speak of religion, is to present it in a way that it is respected and appreciated by the other. The Crossroads of African Cultures (CCA) had the opportunity to reflect on this subject. It is then necessary to return to the values of traditional culture and religion to find elements that can help to present religions in an acceptable way. Africa’s religions and sociology are not a history of hostility to religious beliefs.

For him, Africa is still at the stage of nation-state building, it is not yet an achievement. At the very least, this is reflected in the way Religion is perceived. The African man has no difficulty in having a supreme being to whom he refers. He respects the ancestors very much and has no difficulty with the concept of “role model“, he is not intimidated, he knows how far to go with the ancestor. It is then that we must also develop the role model approach of African people who have lived in the encounter and openness of other beliefs. We can talk about Léopold Sédar Senghor and his commitment to the encounter of beliefs. Ex: In Nigeria, the water divinity Oshun is considered as a role model. These “role models” are a source of peace.

Exchanges of views and perspectives

A member of the public makes a comparison between Africa and France in the teaching of religion. In contrast, in Africa the state does not fight the religious fact and tries to organize coexistence. We would like religion to be private and it doesn’t make sense because worship is public.

Another remark is made, religion is a great issue for man. Instead of dealing with it through the human issues it raises, religion is treated as a problem. So how do we talk about it in the end ?

Professor Nouailhat proposes some ideas that he had already mentioned earlier: the expression “religious facts” was found to reintroduce religion without making it clear. Religions should also be treated as such: but to whom should the mission of talking about them be entrusted? In Alsace Moselle, there are courses in religion by people trained by the state (which awards diplomas) but there is nothing similar in the rest of France. Treating them outside the school leaves room for all charlatans, because there are people who take advantage of ignorance to exploit religions. In the past, the Catholic Church offered a kind of public service in this regard (children were exempted from classes on Thursdays in order to be able to go to catechism). The lack of training in religious matters has serious consequences for “living together”.

Denise Lemann takes the opportunity to bounce back on these words and share her experience. She told the assembly that in Catholic schools, people talk about faith and spirituality so as not to frighten the world (the fear of manipulation is very present). People must take ownership of the religious fact from their quests. She proposes the following approach for Africa, according to her, one way to approach the religious fact on the continent would be to make a spiritual reading of the scriptures instead of taking them in a scientific way. She feels that people are sometimes a little afraid of the scientist. Then we could combine the two and have a little choice. In Latin America this living faith is important, this deep conviction that God is there is omnipresent.

This is an opportunity for Ms. Bardette Monette, who works in public education, to give a testimony related to her experience. She deplores the inaccuracy of some teachers’ comments when they talk to students about religions, which echoes Professor Nouailhat’s comments when presenting the teaching of religion in schools. Moreover, she deplores the fact that she cannot correct these remarks because this would be contrary to the authority of the teacher. That’s why she fears that students will eventually develop “cathophobia” in France. According to her, France could take inspiration from Canada, where the teaching of religion is abundant, in order to “reconcile with its religious heritage”.

An interesting proposal for a comparison with China is proposed by Hong Bing Yang, a member of the IAM, to enrich the different perspectives on the issue. In China, we don’t talk about religion. Master Chin Kung said in this regard “the term religion, we must not mystify it, in China it means the fundamental teaching of life”. A question then arises: does this simplify the teaching of religion in schools? No answer is given to this question, which remains open to reflection. Hong Bing Yang suggests that a “demystification of the word” would facilitate its teaching. Our two speakers remain doubtful about this solution. For them there are several ways in this basic education.

The question of the hyper-development of science in the West as an obstacle to religion is raised: “Did he make people believe that they can create their God? A member of the public suggested “rearming so that we can talk openly about religion”.

The various other models that exist in the teaching of religion and the possibility of importing them into France and Africa are then discussed. The example of the Havard divinity school “world religion” which is the subject of Jesuit supervision is given. This school conducts research on all religions that have a good reputation. Why not import this model? Denise Lemann, teacher, proposes the creation of an international centre that would do the same thing and not just import this model into France where the question of religious education remains quite delicate.

Concluding remarks

In order to conclude and reflect on the latest contributions of the public, Father Basil Soye shares with us his commitment to the training of young Africans in respect for beliefs. According to him, the greatest danger of religions and secularism in Africa are politics and the fight against fundamentalism. There is the secular French model, but there are others from which Africans can learn. Secularism as conceived by France is explained by the context of things, which makes it difficult to export it elsewhere.

Synthesis written by Mrs Diaby Aminata