Africa is a paradoxical continent, it has important energy resources (oil and gas, hydro and solar energy potential) and yet a significant part of its population suffers from energy scarcity. What solutions can Africans find to get out of this situation? It is useful to take stock of this issue which has been on the agenda for too long.

In its “Agenda for 2030”, the UN adopted, in September 2015, 17 goals for the sustainable development of the planet to be achieved by 2030. The seventh goal concerns energy: “to ensure access to adequate, reliable, sustainable and modern energy services for all at an affordable cost”. The UN also recommended “significantly” increasing the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. This objective specifically concerns Africa, to which the International Energy Agency (IEA) devoted half of its 2019 report, the World Energy Outlook 2019 (www.iea.org, November 2019), and highlights the challenges it faces. In 2018, Africa had 1.3 billion inhabitants (1.1 billion in sub-Saharan Africa), i.e. 17% of the world’s population, but its consumption represented only 6% of the world’s energy (3% for electricity). Per capita energy consumption in most African countries is far below the world average, i.e. about 0.7 toe (tonne of oil equivalent) instead of 2 toe, and they contributed only 3.6% of global CO2 emissions. While bioenergy (mainly wood and plant waste) accounts for 45% of Africa’s primary energy demand, it is not without resources : Hydrocarbons account for 39% of its primary energy mix and coal 13%, it has a very significant renewable energy potential and “critical” metals that are indispensable to energy sectors such as cobalt, chromium, uranium and platinum. Moreover, 40% of the discoveries of gas deposits between 2011 and 2018 were made in Africa (notably in Mozambique, Egypt, Tanzania, Senegal and Mauritania).

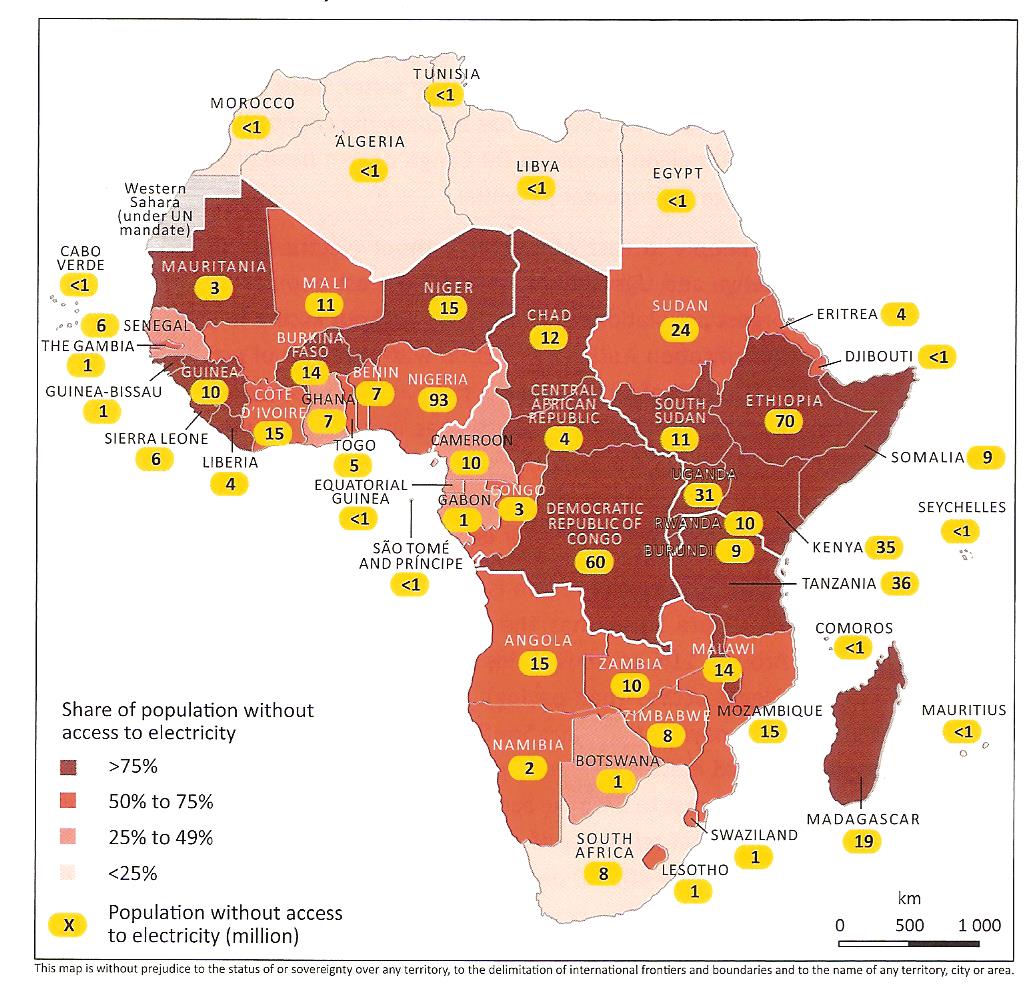

Two major findings should be added to this table. The first is that 600 million people in sub-Saharan Africa do not yet have access to electricity, as the electrification of North Africa has been completed (see map, IEA, 2019 report, p.362). It is true that countries such as Ghana and Kenya have made a very significant effort (84 and 75% of their population “electrified”). The second is that about 900 million Africans do not have the possibility of using “clean” energy for cooking, the majority still using primitive stoves (made of several stones and without chimneys) using charcoal, vegetable waste or kerosene as fuel and polluting the atmosphere. Nearly half a million premature deaths are attributed each year to this pollution, which is the cause of respiratory diseases affecting mainly women (who cook…) and children. Progress is being made on both fronts (20 million Africans have gained access to electricity every year since 2014, but the population is growing…). The growth in energy consumption in North Africa, Nigeria, South Africa, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo have contributed significantly to that of Africa since 2010 (a 50% growth in the latter two countries).

The complete electrification of Africa and access to clean and sustainable energy for all its inhabitants are two major challenges for this continent whose population will increase as it becomes more urbanized (the IEA envisages a growth of nearly half a billion people in cities with nearly 2.5 billion inhabitants in Africa in 2050 according to the UN), urbanization will increase energy demand. The IEA considers several scenarios in its 2019 report. Thus in the so-called “Advanced Policies” report, it takes into account the energy policies adopted by the States and assumes an annual growth of 2.1% in energy demand and 3.6% in electricity demand by 2040. It proposes a more dynamic variant, called the “Africa case”: it would ensure universal access to energy for the whole of Africa, in particular to electricity as of 2030 (in 2025 for Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia and Senegal), which assumes a 10%/year growth in production, which is considerable, and greater energy efficiency.

What energy options are open to Africa ? The first is the conventional use of fossil fuels to generate electricity in thermal power stations and the use of liquefied natural gas in modern cooking stoves, but these will come up against the objectives of the fight against global warming. The second is the large-scale exploitation of its renewable energy “reserves”. Its hydroelectric potential is significant, particularly in the Congo and Nile basins (see photo of the Renaissance dam on the Nile, hydroelectricity provides half of the electricity production in sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of electricity is produced with coal in South Africa). According to the IEA, renewable energies would ensure, depending on the scenario, from 46% to 75% of the electricity production in 2040, the share of photovoltaic solar energy and wind energy (important on some coasts) would be 20 to 40% while it was only 2% in 2018, we can see the importance of the effort to be made; hydropower production would double in the “Africa Case” scenario but its share would decrease. Photovoltaic solar power is well suited to rural areas far from large electricity grids but one can imagine building mini-grids around solar power plants (Morocco is developing concentrated solar power plants cf.photo).  For cities, often megalopolises such as Lagos, Abidjan, Luanda and a few others, their electricity supply via power lines connected to large power plants (gas-fired, dams, off-shore wind turbines on some coasts) is inevitable (cf. photo in Kenya). Finally, abundant biomass (cellulose from plant waste in particular) can be used to make biofuels. Innovations are being implemented to distribute electricity on demand in some countries such as Kenya: companies install solar panels in a village as well as a mini-grid, households can consume a few kWh on demand, which they pay for with a smartphone (they can rent a solar kit with a panel they install and pay a rent).

For cities, often megalopolises such as Lagos, Abidjan, Luanda and a few others, their electricity supply via power lines connected to large power plants (gas-fired, dams, off-shore wind turbines on some coasts) is inevitable (cf. photo in Kenya). Finally, abundant biomass (cellulose from plant waste in particular) can be used to make biofuels. Innovations are being implemented to distribute electricity on demand in some countries such as Kenya: companies install solar panels in a village as well as a mini-grid, households can consume a few kWh on demand, which they pay for with a smartphone (they can rent a solar kit with a panel they install and pay a rent).  The fragility of electricity grids is, today, a handicap for the African economy which it will have to remedy, in particular through interconnection on a regional scale. The annual investments required for electrification are considerable, currently amounting to 21 billion dollars, but they should rise to 45 billion dollars in the “advanced policies” scenario and to 100 billion in the “Africa case” scenario, which is considerable and assumes international financial engineering.

The fragility of electricity grids is, today, a handicap for the African economy which it will have to remedy, in particular through interconnection on a regional scale. The annual investments required for electrification are considerable, currently amounting to 21 billion dollars, but they should rise to 45 billion dollars in the “advanced policies” scenario and to 100 billion in the “Africa case” scenario, which is considerable and assumes international financial engineering.

The energy transition is necessary in Africa as in the other continents (with the objective of eliminating their still very low CO2 emissions) but with the need and urgency for it to have access to modern energy (the seventh objective of Agenda 2030). This transition will pose two problems. African oil and gas exporting countries will be affected by the “decarbonisation” of energy as many of them are highly dependent economically and socially on export revenues, which account for the majority of their fiscal revenues. This is the case for Algeria, Nigeria, Angola and, in the near future, Mozambique, yet most of them are not prepared for the energy transition due to a lack of investment in the industrial sectors. This transition also involves the use of renewable energy sources and therefore the mastery of new techniques (solar cells, wind turbines, electricity storage, etc.) very often covered by patents belonging to companies or public research institutes located, for the most part, in Western countries and China (Cf., C. Bonnet, S. Carcanague, E. Hache, G.S. Seck, M. Simoën, Towards a more complex geopolitics of energy? IFPEN, IRIS, ANR, December 2018, www.ifpen.fr ) which can block technology transfers to Africa and their access to renewable energies. A research effort is essential to avoid this blockage. These energies and the “critical” metals necessary for their use (such as platinum and cobalt, with which Africa is very well endowed and are an asset that it must play) will be an important dimension of a new geopolitics of energy of which China intends to be a leader (it is trying to sell a coal-fired power station to Côte d’Ivoire that neither the World Bank nor the African Development Bank have agreed to finance…).

Let us conclude this panorama by recalling that the global “energy landscape” has changed since the beginning of 2020. The price of a barrel of oil was close to $61 in January and since then it has collapsed in “two stages”. The first was a rapid fall in early 2020 caused by the price war that Saudi Arabia, Russia and some other OPEC producing countries have been waging for the past year to gain market share and make US shale oil production vulnerable. The second occurred in early April when the coronavirus pandemic affected a very large number of countries, China being the first, which applied containment measures leading to the shutdown of a large part of their economic activity and consequently of the demand for energy, electricity and oil. Oil production collapsed with it, its price fluctuating between $25 and $30 a barrel, at the beginning of May, as the IEA anticipated a 10% drop in world production in 2020. This collapse affects of course the entire world oil industry whose revenues are falling, but also fragile exporting countries in Africa, notably Algeria, Nigeria, Angola, Gabon, Chad, Equatorial Guinea and the two Sudan, whose export revenues are a critical resource for their budgets (70 to 90% of their budget revenues), while they must implement urgent social and health measures in 2020.

Energy poses a real challenge to Africa. It must both build infrastructure to ensure that the entire continent has access to modern energy, with priority given to electricity, an essential prerequisite for its social and economic development, and prepare to eliminate fossil fuels from its energy mix, exports of which are a major source of revenue. It can cope with this by finding continent-wide solutions.

Source: “Un blog de Pierre Papon” (French)